In My Solitude

3102-11-02

Without knowing or asking why, I’ve inched my way halfway to seventy. Further now, actually. I say without asking why, and that’s not at all true in general, but in particular I have not asked the question of why senescence? Myriad questions but never that one. Still now, I’m not all that curious about it.

3102-11-03

There’s never enough. At first, the sweat seems like enough. You’d rather not sweat, but you will if you have to. Then you get used to sweating, and it’s not enough. You know you can cry if you must, but you’d really rather not. But then crying, like sweating, is part of it, and the tears and sweat are not enough. You know there’s blood. God knows, there’s blood, but you really don’t want to dip into that. Where do you go after that? But you do dip, and then there’s blood. And still, it’s not enough. So then there’s the marrow …

Go here, then come back. It was originally titled “A Situation,” just fyi.

And now …

I listened to the smoky voice, if somewhat silly sounding, too, over the sounds of the piano. The voice giving way at times to masterful trumpet, and I’m reminded of my own solitude.

It was a time when I could not leave the house for more than a few minutes without feeling like I might die. I could go to the grocery and sometimes to the movies, but that was about it.

I knew that other people did not know. I’d spend lots of time on my looks and gauging other people’s reaction to them. That, in time, I learned was part of the problem, but then I drew some comfort from knowing that I at least looked good, and no one was the wiser.

It was a fabulous time for painting and for filmmaking. I made my first two films that summer, completely autonomously. I painted a series of about eight paintings on canvas with mostly acrylic paint, though some were mixed media. They weren’t commercial so made no money, but it was the genesis of my life as an artist, among other things.

Writing was underway as well, and my identity as a writer was still strongest, though I could tell I was failing to mature in my goals toward becoming a professional. Part of how I dealt with this was to tell myself that I had no real interest in being a professional, that writing for myself alone’s enough. The work would someday find an audience … or not. In any case, I’d likely be dead by that point.

That’s what I told myself but didn’t believe it. I believed, secretly and deep down, that I would one day work it all out and be recognized, even if for a moment, and even if only by a few, for my unique perspective and for the one or two things that I thought I did well, and that maybe even somehow I’d find a way to craft a life from it.

Painting was simpler because it wasn’t as much of my identity. I hadn’t had long talks with my grandmother about becoming a painter, nor had I won any painting contests as a child, nor did I excel in art class, nor did my friends and family come to think of me as the resident artist, nor did I introduce myself to people as a painter, or at least an aspirant painter. Not then anyway. Later, and gentler still, I would say something like, “Yes, I paint.” And would qualify it like, “But I’m an amateur.”

Writing, it would seem, was not only more of an identity but a fractured one. The writing which others seemed to respond most favorably to was autobiographical—at least a little—or poetry. I was not really a fan of either of those things and had only written the pieces under assignment. I was a genre writer, in my mind, but lacking many of the conventional skills of genre while also being displeased of the familiar trappings of genre, wanting to breathe new life in without fully having explored the cavernous depths of the known world.

No audience; that was always my own feeling about why I would stop and start but never run continuously. I also tired fairly quickly with the marketing process. It was not until I found my professional calling elsewhere that I found a fondness for marketing, and even still adapting it for writing was cumbersome.

All of my work is art, no matter what the medium or service, and it is all very personal. But none so personal to me as writing.

Some mere aspect of myself began to emerge during this period of solitude, this time of the great turning, let’s say it was 3100, though that’s not really accurate. I learned to rewire my nervous system without instruction. I suppose you could argue that I’d found blueprints of sorts, but the implementation was all my own. With this rewiring came a surge of fearlessness. I confess, I used chemical augmentation for a brief time until I knew the system would be stable. I jumped out of the sky that year, and would race along the blurring lines of the rolling hills along the way to the harbor and back without much thought of death. Even though I felt on the edge of my own salvation or destruction, that paper thin precipice of unforetold future, I felt firmly alive and healthy in my core. This was when I was young still but feeling older than I was. Much like the sick mind thinking well and the well mind being sick, I was the young mind thinking old, feeling old.

The rain-slicked streets with red running along them in the midnight sky stand as signposts in my memory for the feeling of total solitude I had then among my friends, my family. I was alone and alien, pretty much completely convinced I was indeed alien. There were rumors of other aliens, but I did not know where to find them. I was the last of my kind, as far as I knew.

Horace joined me in my solitude that year. He’d been my best friend since we were about ten. Or he was ten, I was eleven. Maybe it was twelve. Anyway, Horace was a mess like me. He was the little sibling and I was the bigger, sometimes the parent, sometimes the pusher. Horace was generally the follower and I the leader, even when I didn’t want to play follow the leader.

That year—what we’re calling 3100—Horace had his shit together a bit better than I did. It’d been going that way, and I was happy for him. He’d been working as a professional (though not really acting like one) and was making good money. He’d cut out all that silly shit that I’d gotten him into, like drink and drugs and all that foolishness. He was still without a companion, but weren’t we all?

“This is a pretty cool game,” he said. “I like that you tied it back in with all the characters we made up before.”

“Thanks,” I said, “I worked hard on it and was hoping you’d like it.”

There were a couple of changes to the game in question that he did not like, but I glossed those over. We played for hours, as we had when we were little.

After a time, “Do you wanna take a break?” he asked.

“Why?” I asked.

“I dunno. I’m getting burned out. Let’s go to the batting cages.”

I felt my throat tighten, my blood race, and thought I might piss myself. This was before I’d rewired my nervous system, you see.

“Let’s just keep doing this,” I said.

Horace sighed. “Look, we don’t have to go out, but I need to do something else for awhile.”

That’s kind of how it went back then. And I felt that feeling of reversal that I often felt with Horace over those three years—that what was once his was now mine. Seeing clearly the same conversation years past next to the pool, my eyes bleary and ready for a change. His alive and eager to keep going. This same memory swell brought with it a tide of other memories of being at that house, by that pool. Johnette singing and limey liquor flowing. Cards and boys and girls and soft images of nudity in the background. Fighting in bed together about stupid shit. Just stupid shit. Waking up awash in the feeling of being grown and alive in a place without context, without a frame other than what would happen next.

“Want to watch a movie?” he asked, somewhat resigned.

“Yeah,” I said. “Let’s do that.”

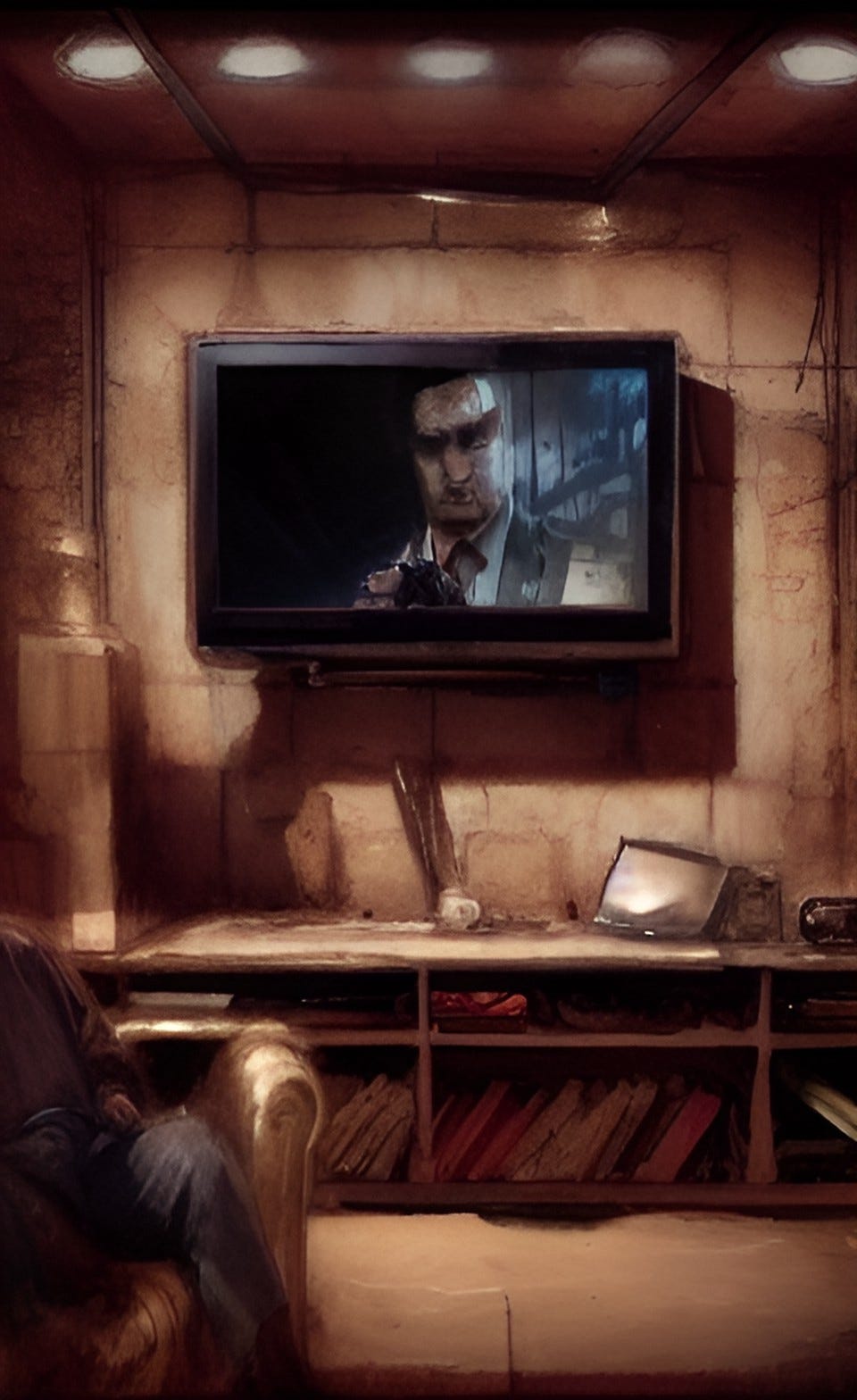

So we did watch a movie, Horace and I, sitting there on the couch down in the underground where I made my nest in those days. Safe underground. Safe from marauders and from pretty people and from cars and trains and flying things. Safe from disease and from disappointment. Safe from human touch and from sharp and blunt things.

I looked at the couch, that graying fabric and saw the memories along the threads. I saw with my alien eyes the memories of the self from before the Blast1—the one who’d left the stage so I could walk in—I saw Horace sitting there at about 14 watching the same movie we always watched when his mother would let him be over at my place. She thought I was a bad influence. I was a corruptor. I was, I suppose, but I was his protector too. I loved him and took care of him as best I could. The corruption was, like data corruption, an accident. It was something that happened as a result of copying others and trying to make a meaningful duplicate experience. Sometimes it worked. Maybe even many times. Other times, it just left corrupted data. And we’d spent years trying to clean all that up.

My eyes led to lines further still in the future of my past, past the Blast forward but still years in my memory now. There we sat in a different house, dilapidated and without proper environmental controls, with threat of bug attack from all sides, yet comfortable in our own way, lost in that feeling of knowing that the next moment would come, sad as though it may be, it would come and be enough somehow. Johnette was there that night. I could still see the tears in her eyes, hurt so badly after what Trout had done to her. She’d sought solace in my arms, which had slid her over to Horace.

I did things like that sometimes. I was on the other side of things again. This time, my affection for Johnette, which had led me to her to start, to brave her beautiful face and put mine in front of hers and ask her if she’d like to see me, to see me as I am with this face again. She was kind, which had surprised me, and invited me into friendship. She’d killed the romance right away, because of Trout, I’d understand, but that didn’t mean we couldn’t be friends.

And it didn’t mean that. We became great friends. I learned a lot through her about my future profession, too. Her brother and sister had neurological problems rooted in the brain, problems that were then largely mysterious. It impeded locomotion and various other functions, not the least of which was socialization with others. They’d formed a kind of collective of the afflicted. I learned through them how similar we all were, even as aliens among the humans, among the pretty. Johnette was human and pretty, but she was some kind of wonderful worker, some kind of emissary to the outcast.

Neurons raced to another time where we sat in my car, suspended above gravel as far as the eye could see. She mused on love and on loss. She lamented her devotion to Trout and how cruel and self-obsessed he could be. I tried, as I would with many women, to be a comfort without imposition. To be there totally and honestly. In truth, it was so; I was as I set to be. But I was also suppressing my feelings for her.

Sounds tight? Well, it was but as time went on, it loosened. The projection fades and I began to see Johnette as she was: a human. I am disillusioned by humans, with all their needs and imperfections and some of her glory had faded. By the time she’d run to my arms, I saw her only as another human, no longer the glory she’d once been.

And I felt a bit cold for feeling this way. And there’s Horace.

Horace had long admired Johnette, and so I introduced them properly, not simply in passing as before. She was of the mind to be received and so he received her. I watched uncomfortably as they entangled on the couch, this graying couch my eyes now trace through time, as the film played out in noisy silence behind us.

Horace was somewhat accustomed to doing this; becoming entwined with a person with whom I’d been involved and in front of me. I think again of Wendy and Horace practically wrestling on my floor.

Wendy, who I had summoned the courage to meet her father, gun on his hip and look at him and tell him I was not the sort he thought I was. He couldn’t look at me, but I had looked at him in all my fear. I knew he did not approve of his daughter finding the tender touch at such long fingers, our long hair blending together like sunlight, soft on soft lips together.

The whole thing was an abomination to him. I was, too, I guess.

The thread runs out as I reach the end of the couch arm, and I see Horace sitting there, now grown, looking at the images. I see them reflected on the surface of his modern eyes. I see him finding meaning in them, not in his life. I feel my stomach swell. I know that feeling. Hell, I practically discovered it for us.

The film faded. Fin. We sat around in somewhat comfortable silence, me still on the couch, Horace on the floor with crossed legs.

He broke the silence, “I’m thinking of moving here.”

“Like, here here?” I asked, startled.

“Well, no. Not here exactly, but down on the coast maybe,” he said.

“Oh,” I said.

“I’m thinking of going back to school,” he said.

“Oh,” I said again.

“You could come with me,” he said. “We could do it together.”

“Oh,” I said, recalling how we’d been down this road before …

… but he interrupted my recollection by continuing: “We could get a place together and split it. I’ve already applied to the Consortium and been accepted. I’m sure you could get in, too. Then we could travel overseas in the summer time. I think after that we could get jobs as …”

I couldn’t keep back the images at this point. The future he forecast was a repeat performance of a past we already had. I understood why he was interested. It had after all worked well enough for him. He’d found a professional job and managed to work in our field. I, on the other hand, had experienced debilitating panic and was consigned to the safety of my underground residence. I made no living; my life persisted as it began at the behest of my parents’ goodwill—a fact they eager to let me never forget. Nor were my aunts and uncles. Nor was anyone, really. It was a drone of drones, like bees swarming my head. That’s about what I could do with it, too.

“I don’t think so,” I heard myself say.

Horace’s face fell into solemn smile, one that was a little condescending and a little bit angry. I knew it well. This was the same guy who’d climbed that tower. This was the same guy sitting in the cold of Wendy’s departure, the air so thin and becoming thinner. This was the guy whose chemicals I’d helped rewrite once or twice and spent years trying to right again. Now he speaks to me with sage wisdom of my folly. And I listen because I need it.

“You’re going to die down here,” he said. “I know you think you’re safe, but you’re not. You’re at greater risk down here than you ever were out there. Your only problem is that you think you have a problem.”

“Listen, Horace,” I said. “I don’t think I survived.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I’m talking about the Blast.”

“What?” he asked.

“You know what I mean,” I said.

I could see his eyes searching through files until he found the one I meant. “Oh. Yeah, I remember, I remember. I’ll never forget. But I haven’t ever heard you call it that.”

“Listen. I was staring at a light bulb the other day,” I said, “and I had this feeling. No, more of a profound understanding that I had not made it. I didn’t survive.”

“Ok …” he said.

“I know, I know,” I said, “I’m sitting here. I’m not an idiot. I can’t account for it past that. It’s just an understanding.”

“That would be really scary to feel that way,” he said. “I mean, I would be really scared.”

“It’s not so much scary as odd,” I said.

“What are you going to do?” he asked.

“I don’t know that there is anything I can do. I guess I’m just going to live this life, whoever I am now.”

My memory of Horace remained as I looked past the window. Wendy2 was laying there covered in paint. She looked up at me and smiled.

“It’s kind of cold,” she said, and I could see her bare skin was bumpy from chill.

I closed the window, shutting out my solitude, however brief it would take leave.