Cinda Ashe

Wendy’s wicked stepmother

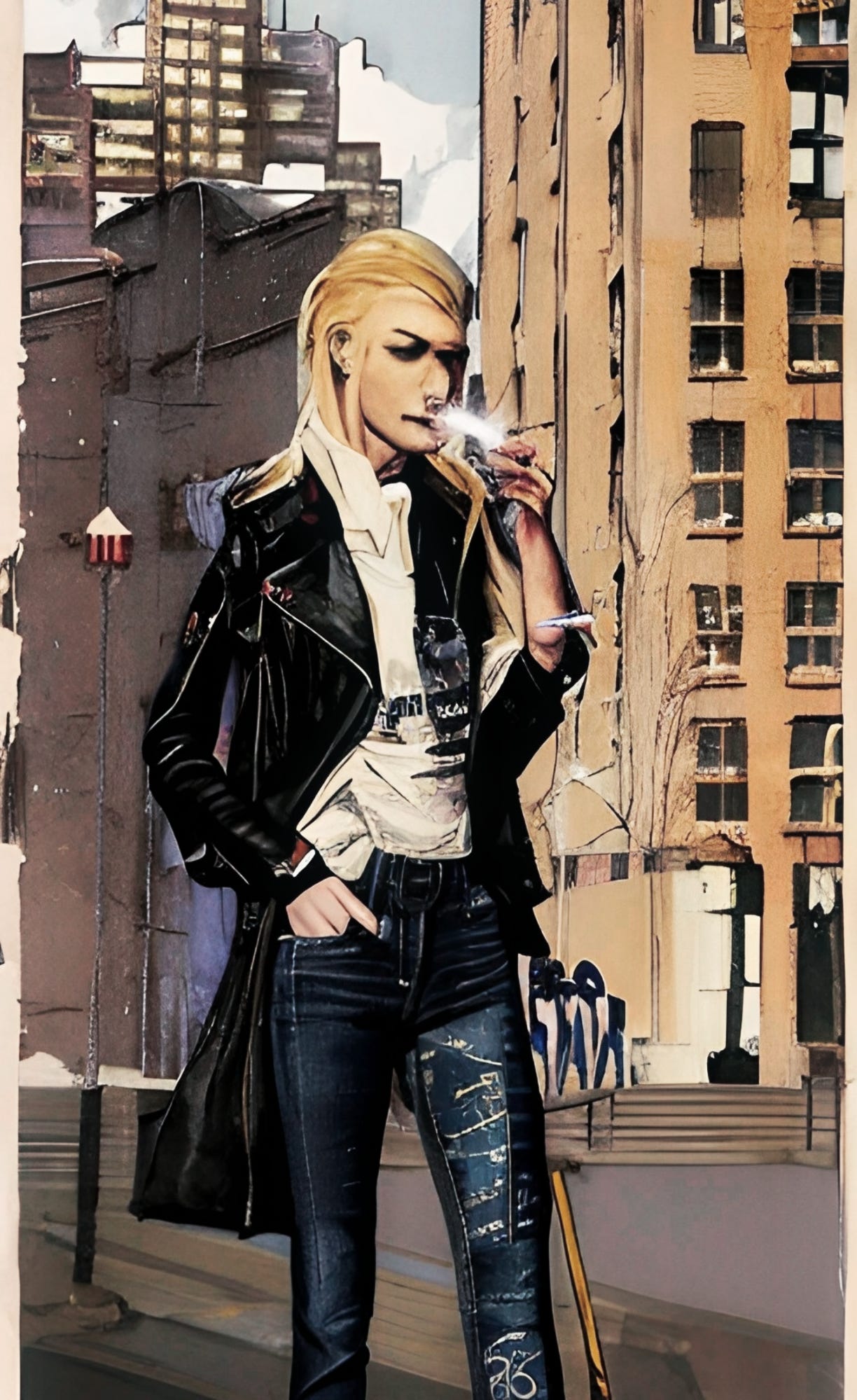

Would it be improper of me to say that Cinda was hot? I thought she was, anyway. A lot of the wrecking crew back there on the Jung thought I was gross for finding moms hot, but. I did. Not because they were moms—at least, I don’t think so, who knows—but because they were fully developed women psychologically. Being the age now that Cinda was then, it feels odd to think that someone in their teens would find me desirable, and I certainly wouldn’t be into it, but. Times are different.

Cinda was hot, I thought, in the same kind of way that a math teacher might be hot. Someone who gets you to stay after school and disciplines the shit out of you. Kind of like a protodomme or something like that. I wasn’t necessarily thinking about all this like that back then; it’s the lens of history narrating more than pure memory. But for the sake of the story and to give you some idea of the type of person I thought she was back in the day, let’s go with it.

One other thing—and this comes from the benefit of being in my forties now and having lived a minute—is that Cinda and Magne were an odd match, particularly at first blush. While Magne was a grizzled old shitdog from the Jungle primeval, a dyed-in-the-wool longstern motherfucker, Lucinda was from one of the preeminent families—the Five Families, we’ll call them—and so would have been expected to partner up accordingly. Clearly that hadn’t happened, and as a middle-aged adult looking back, I can only infer the kind of shitstorm their own getting together brought about, and it casts their view of my relationship with Wendy in a different light, doetn’t it? But when you’re a sullen kid on the Jung, you don’t notice these things. You’ve been in this life for about forty-five minutes and it already feels like for-ever. And what you don’t know fills a goddam library. So there’s that then, the context of the pairing of Wendy’s dad, the take-no-shit bastard Magne, with her imperious and refined stepmother, Cinda Ashe.

The Five Families were littered all throughout where I grew up on the Jung. There offshoots, too—two of them I knew of—who were like the black sheep. Many of the career criminals and bad-wired hardcases were from those two families, while all the leaders, luminaries, and wealthy folks belonged to one of the Five Families. I was friends with a few of them and didn’t know it—not at first. Most of the time you could spot them a mile away, covered in silver and gold, all the best clothes, the best cars, the best best best blah blah blah. And it was easy to see why people would like them or hate them, but mostly I found them annoying, an ostentatious obstacle to walk around in the hallways. And they caught one look of my black leather and lips, one whiff of my smoke-drenched passage, and they wanted to step aside. That was the idea, right?

When we were dating, Wendy and I, somehow I’d gotten the impression that Cinda was an artist. Or maybe an art critic or art historian. Something rarified like that. But no, I was wrong. She was, in fact, a coroner. I suppose that’s how she’d met Magne, though I don’t really know how they met. This leads me to wonder if she ever examined Wendy’s body, so I think we should look into that at the Somatic Hall of Records. Or should it be the Hall of Somatic Records? Whichever. That’s where we go.

We speak with a foxy clerk there, and they help us to the part of the facility we need.

Therein, we find the reports of Wendy’s death. They are strikingly spare.

The coroner’s report was signed by someone named Dabney A. Dodger, with the title ‘capitae custos placitorum coronae’ typed under the signature line. But it also indicates that ‘additional consultation of evidence’ was provided by B. Lucinda Ashe, ‘vicarium caput.’

“So she did examine the body,” I say aloud.

Someone shushes me.

I frown and look at them, then resume reading the report.

There isn’t much more to get from it. She died due to the crash. Head trauma. Broken arms, broken legs, broken ribs, broken everything, basically.

It feels odd to have this document in my hands now, knowing that it has been here all along, open to the public, and I just … never looked. In my defense, never thought to look, but.

With a sigh, I reseat the report, close it, and put it away.

I tousle my hair and adjust my bag. If you’re with me, I motion for you to come on. I glare at the shusher as we pass them. They don’t look at me, which I’m sure is intentional.

Once we’re back outside, I exhale and dig around in my bag for cigarettes.

“Well, that was a fucking waste of time,” I say, still digging around in there.

You might try to be supportive and disagree, pointing out that we didn’t know for sure Cinda had examined the body, but now we do.

I shrug, keep looking in the bag.

Finally, I find the pack of Kamel Red Lights, retrieve them, pull one, stick it in my lips, light up.

You ask me why I started smoking again, and I say that it isn’t easy living alone inside your own cells for seven years.

“Plus I don’t think I can get sick or die in here,” I say, looking around, off into the distance. “But. Not sure. Haven’t tested it.”

Perhaps you think I should, or maybe you say it’s good I haven’t and urge me not to; but, in any case, I just wave it away, take another drag, and say, “Let’s go interview this rich bitch sawbones.”

We whir through the city streets, then turn down south, down below, out to the deep clan Calvados.

Out there in the cleared Jungle, there’s some hills and lots of grass. Everything is manicured, but not like sculpture exactly, not like topiary; that would be gauche and gaudy. No this is engineered to give the impression that the natural Meezed is a flawless beauty, that the denizens of the clan-lands are, in fact, the chosen people living in their chosen land, a blissful quasi-tropical utopia of pearly-gated estates, wide-deep-long manor lawns, and ‘wild’ plant life that gracefully eases itself over the manmade bits. It’s a show, a farce, a set.

I am narrating all this as we drive, to your amusement or annoyance or whatever. Go back and reread the last paragraph with that in mind, you know, if you want to.

If you’re keeping count, well, you lose count of how many such places there are, perhaps giving you the mistaken impression that Soma is rich with wealthy inhabitants.

“Oh my no,” I say. “It’s all an illusion. There’s, like, five families out here and a few hangers-on. It’s a con. Old Whitey still doin’ his thing.”

You ask am I not white, and I just smile and light another cigarette.

After what feels like an hour, we reach our destination: a palatial estate surrounded by gating and tall trees.

We stop at the front gate. You may not have been paying attention to the music that’s been on, but you notice it now:

With a flick of my finger, I roll the window down, let the robot intercom scan my face.

I gesture around in the air, presumably at the trees, and say to you without looking at you since my face is being scanned, “There are turrets and shit up there. Like, if we tried to climb over … hamburger.”

You might look in the general areas I motioned to, but you cannot see any turrets.

The robot intercom speaks in a human-sounding, pseudofeminine voice: “Ministry of Secrets private operative Master Secretist Willa Teresa Anderson, S.O.S., authorized for general clearance. Issuing request …”

Willa? you might ask.

“Don’t … worry about,” I say and wave it away, stub my cigarette out in the ashtray. If you’re too young to know, cars used to have ashtrays built into them, usually under the stereo.

The robot speaks again: “Request granted. You may proceed onto grounds. Be prepared to surrender all weapons upon arrival.”

You ask if I have any weapons on me, and I say, Not anymore. I’m one hundo nonviolent these days.

I add, “If you have any on you, though, better leave ‘em in the car.”

The gate parts, opening up this little piece of horrible heaven to us, and we drive on through.

You can see the house from the gate, but it looks quite small in the distance. As we close, it keeps getting bigger and bigger, until once we’re upon it, you can see it is massive.

I park Vengeance, and we get out.

A butler lookin’ motherfucker approaches, and I reflexively put my arms out to my side and he begins frisking me. He runs a scanner over me, then does you, tells both of us we’ll be scanned again when we walk in by built-ins, continuously scanned and monitored whilst inside, and scanned and frisked once more by him when we leave.

I shrug and light a smoke. Then I think, Fuck, maybe I shouldn’t have.

Almost as though he can read my mind, he says, “Smoking is allowed on premises. Quite all right.”

“Oh, word?” I say.

“Indeed,” he says. “Madame smokes quite a lot.”

“Right on,” I say.

“If you’ll come with me, I’ll get you fully processed and inside.”

He leads up to an intricate gold door, opens it, and holds it for us, waiting until we are inside to close it behind us. It seals with a magnetic hiss-click, that makes me look at you and flick my tongue vulgarly.

You react to that however you do.

I whisper to you, “I just remembered that she has one wonky eye, so try not to stare it.”

Perhaps you find that distasteful, or maybe you wonder why in a world where bioidentical replacement parts are readily available for the rich, she had not simply gotten a new eye.

Either way, I shrug. [Ed. see below, play procedures.]

The butler-y dude gets us to sign a book, then does a retinal scan, a palm print, a thumb, just everything shy of bodily samples.

After he’s done his duty, he smiles and gestures for us to proceed.

We take to the great hall—what I suspect is one of many—and then the butler guy hurries ahead of us and directs us through a short series of halls, each lined with paintings, pictures, holograms, and statuary. All of it gives the impression of great refinement, of supreme love of beauty and art.

I gesture around and say to you, “This is all bullshit. These fucks don’t give a shit about art.”

You probably already know that, and react however you do.

The butler-like fellow opens a door that itself almost looks like a painting, and bows his head, his arm holding the door ajar so we may enter.

We do, and therein we find the old battleaxe herself, Lucinda Ashe.

She’s standing near the mantle of a fireplace, of which there are three in the room. Her posture gives us the impression—or is supposed to, anyway—of deep thought and reflection.

My fancy eyes see right through that shit. You may too, I dunno. [Ed. v.i., play procedures.]

“Lucinda Ashe,” I say, kina like a cop in an old hardboiled film.

She turns at the mention of her name, a sort of startled expression on her face, as though she didn’t know we were coming and hadn’t arranged for our entrance and all that.

“Yes?” she says with an affected kindly innocence, the sort you might expect from a gentle elder at a grocer or something.

“I’m Teresa Anderson,” I say. Then I introduce you, however it is you like to be introduced.

Lucinda smiles, more knowingly this time. She says, “Well met, secretist. Please. Call me Cinda. Everyone does.”

I smirk and nod. “Yeah, okay.”

“Won’t you two please sit down?” She asks it, but it’s a demand. A demand of courtesy. Of gentleness. Or genteelness. That sense of ‘gentle.’

“I suppose it is,” she says. “Won’t you indulge an old women her petty eccentricities?”

Fuck, I think. I was narrating aloud again. Hate it when I do that.

“It’s quite all right,” she says. Then, she moves toward a sitting area within the larger parlor.

We follow.

I specifically think, consciously restraining my mouth, and ask you telepathically: Is she reading my mind? Or am I speaking without thinking again?

If you haven’t locked telepathy yet, you probably just see me making at face at you and react however you do.

She sits down in this posh-ass, throne-looking joint1, and we each take a seat opposite her.

Which, you know, is apt.

“So,” Cinda says, “what brings you out so far this way today?”

I cut to the chase, which has already gone on too long, right? For decades now.

“Wendy,” I say.

“Ah,” she says. “I should have known as much. What about poor Wendy?”

“You assisted in the examination of the body,” I say.

“Did I?” she asks.

I nod. “You did.” I show her a copy of the report we got from the Hall.

Cinda glances as it with feigned disinterest, then smirks. “I suppose I did. It says I did right there I did.”

“What do you recall about it?” I ask.

“Oh not much. I’ve seen a thousand dead hellions since then.”

“But this is the only stepdaughter, right?” I ask.

She nods. “The only stepdaughter, yes. But not the only wild child who met a grisly end.” Cinda rubs her thumb and forefinger together, looks at that point of contact, and asks, “You were one, yes?”

A kind of heat crawls along my scalp, and my face gets tight. “What’s that supposed to mean?” I ask.

“What was it you called yourselves?” She pretends to think it over, like she’s having to struggle to recall it. But I know she knows. “The Wrecking Crew, was it?”

I glance at you briefly, then say, “I think you have me confused with someone else.”

“Is that so?” she says. “I have access to your whole service record, Wil.”

“Wil is my father,” I say. “I'm Teresa.”

“Right,” Cinda says. “Tracy. I remember you. Of course I do.”

“What do you mean by that?” I ask.

“Let it drift,” she says. “I know who you are is all I’m saying.”

I look her in eye, the one that is mobile.

“You’re the one who was that little heroin chic waif.”

“Right,” I say. I’m not confirming, just acknowledging what she’s saying. She knows it. I can see it in her eye.

“Her father really hated you,” she says.

“I’m not sure he knew me,” I say. “I think he, too, had me confused with someone else. Someone I’m not.”

Cinda shrugs. “That man hated everyone, whether he knew them or not.”

“Hated?” I ask.

“Yes,” she says.

“So he’s passed on, then?”

She smiles. “I’m afraid so.”

I look at you. If you have telepathy, I ask you to make a note of that.

“Gone, oh, almost twenty years now,” she says. With her old but still sturdy hands, she lifts the lid to an ornate cigarette box on the end table next to her, retrieves a hand rolled cigarette, lights it with a silver lighter that is shaped like an anatomically correct human heart. After a nice long drag, she says, “He was a good husband. Well … good enough. For me.”

I wonder about that, but skip it. “How’d he die?”

“Out in the yonder. In the deep jungle, they call it, yes? The long bush.”

Her smile is starting to get to me. “Yeah, that’s what they call it.”

“He always knew,” Cinda says.

“Knew what, exactly?” I ask.

“That the dirty shitbags of this hellhole would get him. That’s what he called them. Dirty shitbags. It’s how he saw people in general, true enough, but especially certain folks.” She smiles, takes a drag, then adds. “Like you. And your little wrecking crew.”

I give it a pass. For now. And ask, “Are you still working?”

“Not officially, no,” Cinda says. “I’m a consultant, they tell me. But I haven’t seen the inside of a laboratory in ages now.”

“How about other financial holdings?” I ask.

“You have access to all that information in the Ministry database, Master Secretist. Everything is filed properly.”

“I’m sure it is,” I say.

She smiles at me—through me, really. It’s all a little game to her, what we go through on this fucking planet.

I look at you, and you can see my frustration, the exhaustion of being in this woman’s presence. “I think we have all that we need,” I say aloud, but I’m speaking more to you than her.

If you want to ask her some questions, you may, of course.

Otherwise, we split.

Play procedures

- ‘Fancy eyes’ is a recurring expression I use to describe a gestalt effect (or set of effects) that allow me to accurately read a person’s intentions, thoughts, and feelings through simply looking at them. It is part behavioral analysis, part intuition, and more generally attention to nonverbal communication. It’s worth noting, though, that in the first book, Everything Fails, I talk about having modified my eyes and nervous system and I get my ex and personal physician, Cobie, to outfit me with a kinetic register, a piece of cybernetic wetware that comes with a complex filtering array and other metacognitive functions. How much of what I understand of a given interaction is due to which factor is usually unclear and varies a bit from book to book, scene to scene, depending upon how much emphasize I want to give to the cyber-y part of da punk. Having said all that, you may have fancy eyes, too, if you wish. Explain how they work, how you got them, or just copy and paste the code from mine. Whatever you want, babe.

- You may already be thinking along these lines, but what might Cinda have gained from Wendy dying? And do you think she had anything to do with her husband’s death?

- You may collect the songs featured in this chapter, or make any reasonable substitution you wish. Soon, I will publish a chapter going into a bit of exploration of how to use the song grimoire.

Story path

Wendy 1 < 2 < 3 < 4 < 5 < 6 < 7 > 8 > 9 > 10

(originally an idiolectic sense) a thing, in this case, a chair; cf. jawn. ↩